Identifying Pressure Points

WHAT IS A PRESSURE POINT?

Pressure points are actors in investment and supply chains that can be targeted in advocacy. These actors can influence the outcome and impacts of a project. They can also help obtain remedies for harm.

The first potential pressure point for advocacy is the company (or companies) developing the project. If the developer does not make changes as a result of advocacy, you can apply pressure to other actors along the investment and supply chain. To do this, you need to understand who these actors are.

To learn how to uncover actors in investment and supply chains, see:

For advice on devising advocacy strategies, see:

A Strong Pressure Point Has Two Basic Characteristics

1. It has the ability to influence the project. In other words, it will have a business relationship with the project, either directly or indirectly. This relationship will be significant enough to give it at least some influence over what happens on the ground.

- For example, a pressure point might be a major investor, financier, insurer or buyer that is directly connected to the project.

- If it is not directly connected to the project, it might be a significant shareholder, financier or customer of the company developing the project.

2. It is responsive to advocacy. In other words, the pressure point will be willing to hear and take seriously concerns about social and environmental impacts. In addition, it will be willing to act on those concerns, principally by engaging with the project’s developer(s) to address concerns.

- For example, a pressure point might be bound by relevant laws or environmental and social policies that are being violated by the project.

- It might have a reputation or brand to protect. Being associated with a harmful project might cause it reputational damage or risk that it will seek to avoid.

HOW TO IDENTIFY PRESSURE POINTS

Successful advocacy campaigns utilize multiple approaches that target a number of pressure points of various strengths. Identifying pressure points and assessing their strength will help you decide which advocacy strategies will be most effective. The following questions can help you determine whether an actor is a pressure point — and how strong it is.

Not every actor will fit neatly into either the “pressure point” or “not a pressure point” category. Many will meet at least some — but not all — of the below criteria. Because of this, it may be necessary to weigh all of the actors against each other to determine which ones are most worth targeting in advocacy — especially if, like many NGOs, your time and resources are limited. The process is part science and part art.

Note that the below questions are general in nature. You can learn more about how to assess specific types of actors, such as Shareholders or Lenders, on those pages of this guide.

QUESTION 1:

How large or significant is the business relationship?

Generally speaking, the more money an actor provides to the project or the company developing it — either directly or indirectly — the more influence it will have. Companies developing projects are more likely to listen to concerns raised by significant investors, financiers and buyers, which are crucial to the long-term financial health of the company.

For instance, a shareholder that owns a 25% stake in a company will have significantly more influence than a shareholder with a 1% stake. Similarly, a consumer brand that signed a longterm, multi-million-dollar contract to purchase rubber from a company will have more influence than a buyer that makes occasional small purchases.

QUESTION 2:

How direct is the business relationship?

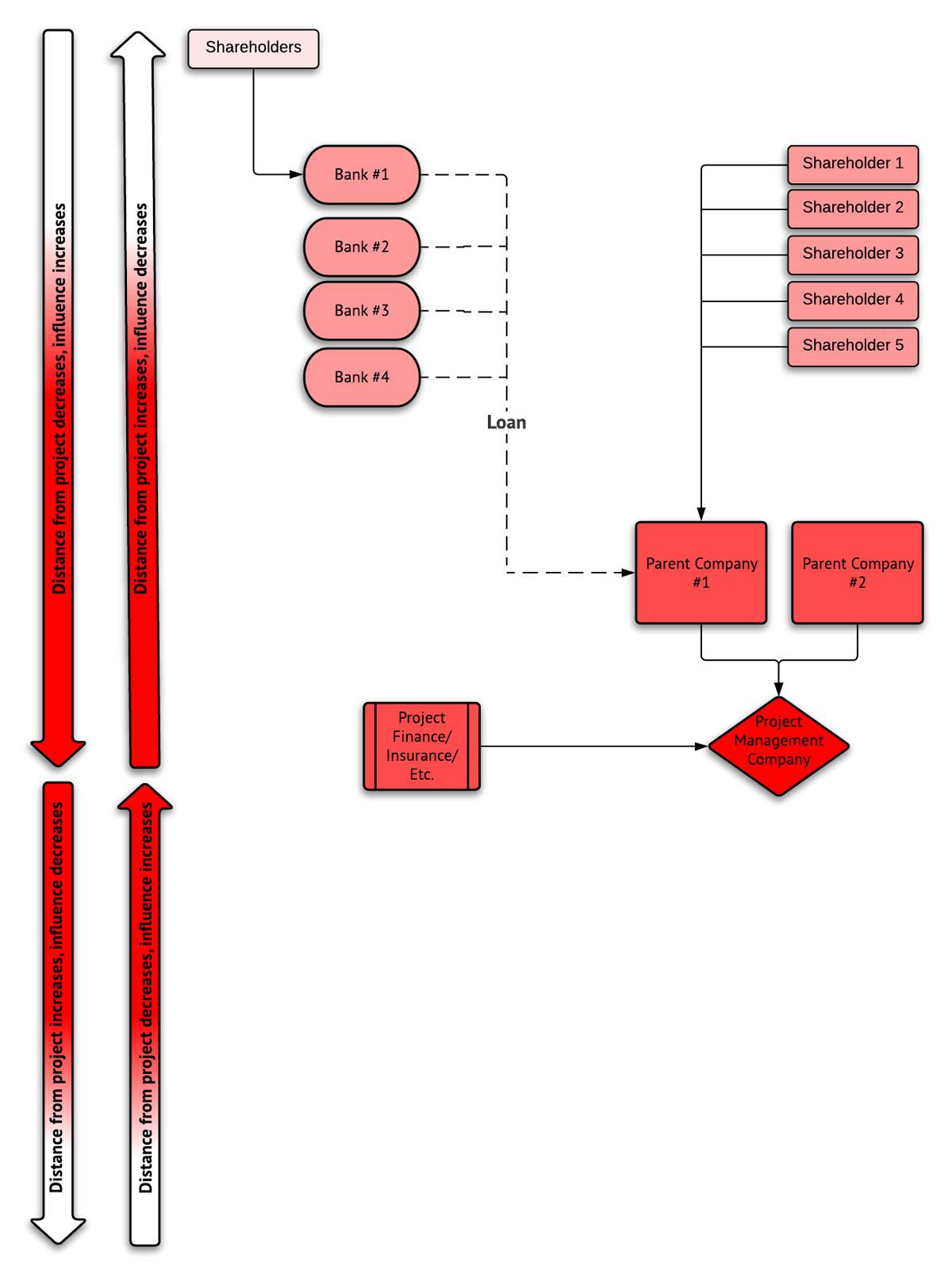

The concept of “proximity” is important in understanding how much influence an actor will have over the project and conditions on the ground.

If an actor has a direct business relationship with the project, it will have substantial influence over what happens on the ground. This includes the company developing the project, banks providing a project loan, and insurers providing coverage for the project. These actors tend to be important pressure points, although the other factors discussed below must be taken into account.

Some actors that are indirectly linked with the project — in other words, separated from it by one or more layers of business relationships — may still be pressure points. For instance, a shareholder of a parent company of the subsidiary developing the project may have some influence over what happens on the ground. But as you move farther away from the project in the investment or supply chain, the level of influence diminishes. For instance, a bank that finances that shareholder may not have much influence over the project.

This concept of “proximity” is illustrated in the graphic below. The closer an actor is to the project, the more influence it will have. Conversely, as you move farther from the project, that influence diminishes.

QUESTION 3:

Is the company public or private?

There are two types of companies: public companies, which are traded on stock exchanges, and private companies, which are not. Understanding if a company is public or private is important to understanding the company’s incentives and decision-making process — and therefore is an important first step toward developing strategies to influence it.

How Are Public and Private Companies Different?

The main difference between public and private companies is how their shares are bought and sold. Public companies are listed on stock exchanges, making it easy for investors to buy and sell their shares. Stock exchanges also make it straightforward for public companies to raise money. But with this access to capital comes an obligation: The company must report important information about itself to the public on a regular basis. Private companies, on the other hand, don’t have to disclose much information to the public. But it is more difficult for them to raise money. Their shareholders tend to be people, often the company’s founders or management.

If a company is public, it is more likely to be sensitive to issues that might damage its reputation. (Although many private companies also care about their reputations.) A bad reputation can have a direct impact on the financial returns of a public company. If a company attracts negative attention, some shareholders may decide to sell their shares to avoid potential financial losses, which can cause the company to lose value. A damaged reputation might also make it more difficult for the company to attract funding.

You can usually find out whether a company is public or private on the company’s own website or through a basic Google search.

QUESTION 4:

Does the actor make environmental and social commitments?

Some actors publicly commit to respecting and implementing internal environmental and social policies. These can be used to hold such actors to account. Companies and other actors that make public commitments but do not respect them face losing credibility and damaging their reputations. The best sources of information on such policies are the actors’ websites, since they commonly advertise these to the public to market themselves as responsible corporate actors.

QUESTION 5:

Does the actor care about its reputation?

Many companies and other actors care about their reputations and are likely to be sensitive to negative publicity. This includes companies with well-known consumer brands, such as Nestle; companies with leaders that are public figures, such as Elon Musk of Tesla; or financial institutions that promote themselves as ethical or “green,” such as the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation.

If consumers do not like the way a company does business, they may decide to stop buying that company’s products or services. Reputational damage can make it harder to attract funding or form new business relationships. This creates incentives to address environmental and social issues. Make sure to do your research: Even if you are not familiar with a brand, it may be strong in other countries.

QUESTION 6:

Is the company registered or based in an OECD country?

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is an international economic organization made up of member countries. The organization’s mission is to promote policies that improve the economic and social well-being of people around the world. The OECD has created a number of standards and guidelines relating to investment and trade, including standards relating to corporate governance and human rights and environmental practices.

If a company is registered in an OECD country, it may be a pressure point because it is subject to the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises. These are recommendations for responsible business conduct. The guidelines are not legally enforceable, but the governments of OECD countries have agreed to encourage businesses based in their jurisdictions to observe these guidelines wherever they operate. The OECD Guidelines apply to all the entities within a business group (a parent company and all of its subsidiaries) that are registered or based in an OECD member country.

The guidelines require that enterprises should, among other things, “respect the human rights of those affected by their activities consistent with the host government’s international obligations and commitments.”

Compliance with the OECD Guidelines is monitored by National Contact Points, which are agencies established by adhering governments to promote and implement the guidelines. National Contact Points can hear complaints from people who allege non-compliance with the guidelines. Though National Contact Points are not always effective as a grievance mechanism, companies that are registered or based in OECD countries may be a stronger pressure point than those that are not.

For a list of OECD member countries, click here.

To learn more about using this mechanism in your advocacy, see OECD National Contact Points.

QUESTION 7:

Does the country where the company is registered and/or operating have strong laws/regulations and an effective court system?

Reminder

Although a large geographical spread can make the investment chain more complex, it may offer more opportunities for influencing the actors, because you may be able to use different laws and mechanisms, including the courts, in the various countries to apply pressure.

Laws set out the rights and obligations of the different actors involved in investment and supply chains. They also shape the rights and recourse mechanisms that are available to affected people. This is the same for the country where the project is located and the countries where parent companies, investors and buyers are based. Some of the laws that might be relevant include freedom of information laws, environmental protection laws, mandatory human rights due diligence laws, and tort law, among others.

In some countries the laws are strictly enforced and there are independent and effective court systems that people can access if their rights are violated. In other countries, what is written in the law and what happens in practice can be very different, sometimes due to lack of capacity or will within a government and the court system. The potential for pursuing legal action needs to be carefully considered in each situation. See here for advice on using courts.

After research and considering the question yourself, it may be worthwhile to obtain the advice of a lawyer based in the country of question. Some organizations that may be able to offer free legal advice are listed here.

QUESTION 8:

Is the company a member of, or certified by, an industry sustainability body?

Certification schemes exist to offer an assurance to consumers that companies are producing in accordance with specific environmental, social or economic standards. Buyers might require that their suppliers implement particular standards or use particular guidelines. For example, a food manufacturer may require that its suppliers’ operations are certified by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil or car companies may require that aluminum they use in their cars is certified by the Aluminum Stewardship Initiative.

Similarly, investors and lenders may subscribe to certain standards for how they spend their money, like the U.N. Principles for Responsible Investment and the Equator Principles.

Some of these schemes also have grievance mechanisms attached to them. This section explains how you can use these grievance mechanisms in your advocacy. If you find an actor along the investment chain that is a member or is certified by one of these schemes, this is a potential pressure point. Many of these schemes have online databases you can use to search for actors in your investment chain.

Inclusive Development International maintains a list of sustainability bodies here.

QUESTION 9:

Is the actor associated with other projects that have caused negative impacts?

When undertaking campaigns or applying pressure to actors in your investment chain, there may be strength in numbers. If a company is involved in other projects having negative impacts elsewhere, you may be able to identify other communities you can work with to apply pressure to the company. Media reports and NGO websites will be helpful in identifying whether the actor has been associated with any other negative projects. Useful sources include Google, BankTrack and the Business and Human Rights Human Rights Resource Center.

Understanding Chinese Companies, Investors & Financiers

Since the mid-2000s, Chinese companies and financiers have become increasingly important in global investment and finance. Chinese actors now invest around the world in a range of industries, including mining, infrastructure and agriculture. In recent years, a significant number of projects involving Chinese companies and banks have attracted negative attention. Chinese companies are often criticized for failing to uphold high standards when operating overseas. However, in recent years various Chinese state institutions have issued statements calling on companies to implement relevant standards when operating overseas, and various policies and guidelines have been issued that apply specifically to overseas projects. While targeting Chinese pressure points can be challenging, community advocates have had some success in recent years.

For further information about how to target Chinese pressure points, see: