Approval and Monitoring of Chinese Overseas Investment

Encouraged, Limited and Prohibited Investment

One of the key mechanisms for project approval is the categorization of “encouraged,” “limited” and “prohibited” investment. These categories were first seen in the Guiding Opinion on Further Directing and Regulating Overseas Investments (State Council [2017] #74), jointly signed by the Ministry of Commerce, National Development and Reform Commission, Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the People’s Bank of China in 2017. The notice was circulated by the State Council, China’s highest administrative body, which made it a high-level policy.

The guiding opinion was issued in response to the increased pace of Chinese overseas investment and aimed to strengthen the top-level guidance of the direction of that investment. To help achieve this, it uses terminology for overseas investments of “encouraged,” “limited” and “prohibited” investment.

“Encouraged” investment has better access to tax breaks, foreign exchange, insurance, customs and information services. For investments that are “limited,” the guiding opinion instructs state institutions to “guide companies to invest in a prudent manner, and give the necessary guidance and reminders based on the specific situation.” “Prohibited” investments are not allowed under any circumstances. Some of the sectors covered by these categories include:

Encouraged

(Section III)

- Infrastructure that will benefit the construction of the Belt and Road

- Investment that promotes export of advanced capacity, high-quality equipment and technical standards

- Exploration and development of overseas oil and gas, minerals and other energy resources based on prudent assessment of economic benefits

- Mutually beneficial agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry and fishery

Limited

(Section IV)

- Investment in sensitive countries and regions, including countries at war

- Real estate, hotels and entertainment

- Investment using outdated production equipment that does not meet the technical requirements of the investment recipient country

- Investment that does not meet the environmental protection, energy consumption and safety standards of the recipient country

(Section V)

- Investment in industries such as gambling

- Investment that is banned by international treaties concluded or signed by China

- Other investments that may endanger national interests and national security

Approval and Filing of Overseas Investment Projects

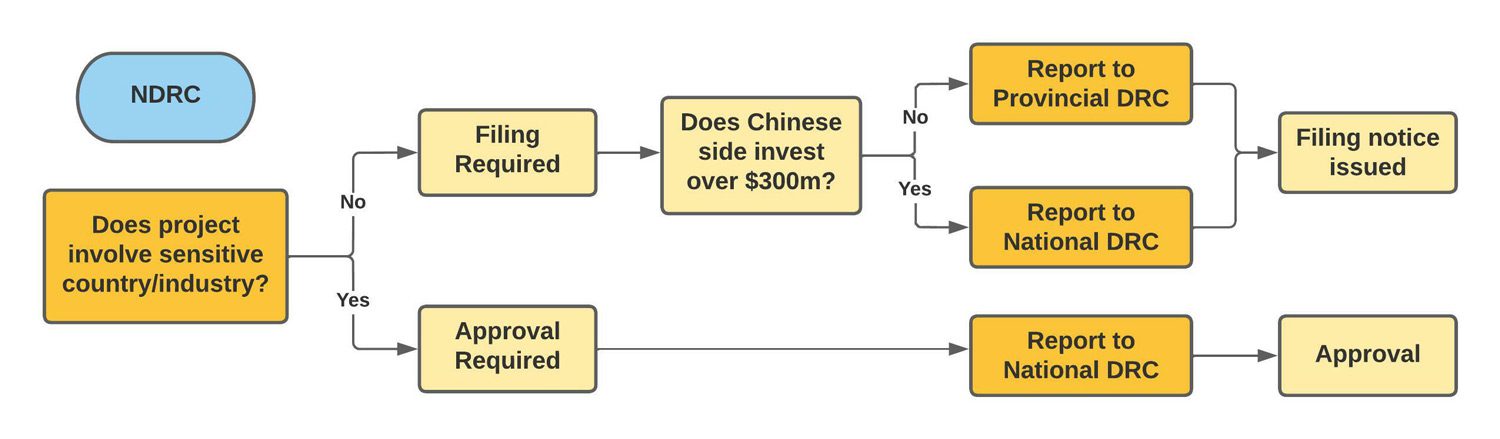

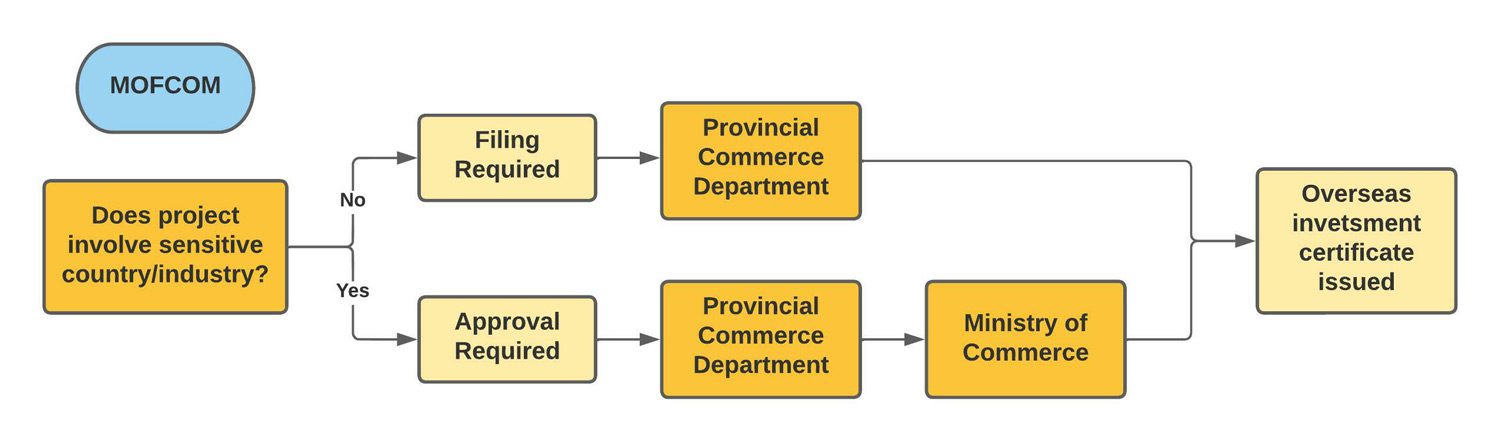

Overseas investments flowing from mainland China need to go through a two-track process of approval or filing with the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) and the Ministry of Commerce. This follows Administrative Measures issued by the Ministry of Commerce in 2014, the NDRC in 2017, and the Ministry of Commerce with six other institutions in 2018.

Under these measures, all investments in “sensitive” countries, regions or industries must be approved by the NDRC and the Ministry of Commerce (or their subnational equivalents). If a project fails to receive approval, the NDRC Measures state that other institutions, including banks, should decline to facilitate the investment (Article 33). However, the screening has been simplified in recent years and the criteria are basic. The NDRC approval involves checking the investment proposal and ensuring it follows Chinese laws, policies and international treaties China has signed, and that it poses no threat to national security or interests.

Other types of investment only need to be filed with both entities (or their subnational equivalents). Filing is a simpler process and involves the investor sending all required documentation. If the documents are in order, the filing is accepted and an overseas investment certificate is issued.

The “sensitive industries” under the 2017 NDRC and 2014 Ministry of Commerce Measures largely reflect the “limited” category set out by the State Council in the table above. Sensitive countries or regions include those experiencing war or civil disturbance, under sanctions of the United Nations or without diplomatic relations with China. When it comes to sensitive industries, the NDRC Measures add exploitation or utilization of cross-border water resources to the list. The Ministry of Commerce Measures define sensitive industries differently, and mainly focus on protecting Chinese technologies, but industries that affect the “interests” of more than one country are also considered sensitive. The 2018 Joint Measures require the Ministry of Commerce and other supervising authorities to develop “encourage + negative lists” of investment to support the approval and filing proecss. The negative lists are expected to clarify the categorization of “limited” and “prohibited” investment. However, these lists are not yet publicly available.

State-owned enterprises are subject to additional approval processes, which are discussed here:

Policies Applying to State-Owned Enterprises

Practical Advice: Engaging with authorities responsible for approval and monitoring of overseas investment

If you have concerns about a project that has not yet begun development, it may be useful to raise it to the attention of the National Development and Reform Commission and the Ministry of Commerce (and its Economic and Commercial Office hosted by the local embassy), as there may be an opportunity to influence the decision to approve or reject sensitive projects.

Once a project has been approved, it is less clear what influence these institutions may have or will be willing to use, but they do have a monitoring role (discussed below). If you engage in communications with Chinese companies, banks or regulators at any stage, it may be helpful to ensure that the National Development and Reform Commission, Ministry of Commerce and other state institutions are aware of concerns regarding a project.

Monitoring Overseas Investment

While relaxing the rules on overseas investment approval, the Chinese government has been strengthening rules for the monitoring of Chinese overseas investment. Recent policies have added requirements on reporting by companies and measures for inspection.

The NDRC and Ministry of Commerce measures both repeat calls for investors to voluntarily fulfil social responsibilities and protect the environment. Additionally, under the Interim Measures for Recording and Pre-approval of Overseas Investment (MOFCOM [2018] #24), investors are required to submit “progress reports” on their overseas investments once they commence implementation (Article 12). These reports should include information on issues including status of compliance with local laws and regulations, protection of resources and the environment, and protection of lawful rights of employees (Article 13). In cases of “major hazardous” or safety incidents, investors are required to report the incident in a timely manner to the relevant authorities (Article 16), which must in turn submit this information to the Ministry of Commerce. The Implementing Procedures for these interim measures require companies to report on emergencies or other significant incidents within 24 hours after they occur. Such incidents include major safety accidents, protests or clashes, and major public criticism.

In addition to monitoring the self-reporting conducted by companies, the authorities conduct regular follow-up inspections of randomly selected companies (Article 19), with the priority being investments of over $300 million, investments in sensitive countries or industries, those that incur substantial financial losses, those in which a significant safety incident or mass protest occurs, or projects that involve serious violations of laws and regulations (Article 18). According to its Inspection Procedures, the Ministry of Commerce checks whether investing or contracting companies have environmental policies in place and implement them, in addition to safety and security management systems, emergency management and fulfilment of reporting requirements, among others. The Ministry of Commerce publishes some basic information on the results of the inspection. Results of spot checks on overseas investment projects can be found here, and results for overseas contracting here. (This information is in Chinese, so you may need to use a translation tool.)

Various other institutions also play an important role in approving and/or monitoring overseas investments. They include the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration of the State Council (SASAC), for central state-owned enterprises, and the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission (CBIRC) for financial institutions. To improve the coordination on monitoring across authorities, the Ministry of Commerce’s 2018 Interim Measures directed the ministry to collate information from these institutions regarding applications, filings and company reporting on overseas investments.

These measures clearly signal the need of Chinese authorities to be informed in a timely way of problems and risks encountered in Chinese overseas investments. However, the regulators currently rely mostly on self-reporting by the companies, and their capacity for inspection is limited given the vast scope of Chinese overseas investment. If you have concerns about a project and the way it is being implemented, you can draw on these policies and urge the Ministry of Commerce and other supervising authorities to ensure that the company in question is reporting accurately, and, if harms arise, to conduct inspections of the project.

Practical Advice: The importance of the Ministry of Commerce

China’s Ministry of Commerce plays a central role in overseas investment. In addition to the mandate of project approval and monitoring, the ministry plays a major role in developing policies and regulations for overseas investment and in coordinating the various state bodies that play a role in overseas investment. It has a department that is specifically responsible for overseas investment, the Department of Outward Investment and Economic Cooperation.

If you have concerns about the way a Chinese company is implementing an overseas project, you may consider communicating this to the Ministry of Commerce via letter, email and/or fax directly to the ministry in Beijing, or via the local Chinese embassy’s Economic and Commercial Office, which is the overseas outpost of the Ministry of Commerce and is obliged to report relevant information back to the Ministry. As discussed in the section Policies and Guidelines with Social and Environmental Requirements, the ministry has jointly issued guidelines on environmental and social responsibilities in overseas investment. If you believe these guidelines are not being followed, this may be a useful entry point for communicating with the ministry.

The Corporate “Social Credit System” and Other Penalty Mechanisms

Until recently, penalty mechanisms for non-compliance in overseas investment have been limited. However, Chinese regulators have been strengthening regulation of corporate conduct and enforcement through the “social credit system,” a diverse patchwork of information collection tools, publicity, incentives and penalties. The corporate social credit system covers some aspects related to the social and environmental performance of overseas projects.

Before the overall framework of the social credit system was published in 2014, the Ministry of Commerce had already explored a “bad credit” rating system and published a list of companies with “Bad Credit History” here, which has not been updated since 2015. Judging from more recent policies, such credit records now appear to be consolidated on the National Enterprise Credit Information Publicity System, the National Credit Information Sharing Platform and Credit China website.

In 2017, the National Development and Reform Commission, Ministry of Commerce and 26 other government institutions issued a Guidance on Strengthening the Construction of the Credit System in Foreign Economic Cooperation (NDRC [2017] #1893), with an MOU on cross-departmental punishment of seriously “untrustworthy” entities. The policy states that companies and banks will have their detrimental behaviours recorded in their credit records, as well as those of the people in charge. Detrimental behaviours include those that violate the laws and regulations of recipient countries, the resolutions of the UN or international conventions, harm China’s reputation and interests, violate the lawful rights of workers, or are involved in money laundering. According to the MOU, failure to protect labor rights, fulfill corporate social responsibilities, protect the environment or respect local customs, can also be considered detrimental behaviors. The policy encourages industry associations and ordinary people to participate in monitoring.

Punishments for seriously “untrustworthy” entities investing abroad include rejection of their foreign investment applications, blocking access to foreign exchange services and deprivation of preferential support from the government. For companies providing contracting services, they can be banned from taking any contracts overseas for a certain period. For major quality problems, a company’s qualification may be downgraded. There are also other penalties that may affect a company’s operations in China, which can pressure the companies to improve their overseas practice. They include restrictions of access to government-supplied land, government contracts, subsidies and other preferential policies. A company’s “untrustworthy” record will be factored in when considering applications for loans and other financial services in the future, as well as for bond issuance and public offerings.

In addition, some departmental rules lay out other penalties. It is unclear how much they can apply to social and environmental non-compliance, but it could be argued that some of the general terms are relevant when communicating with Chinese authorities, especially when their social and environmental practice can potentially lead to “serious consequences.” For example, in cases where a project threatens the “national interest” of China, that project may be suspended by NDRC until corrective action is taken. Penalties by the Ministry of Commerce for violations of regulations that lead to “serious consequences”—which is undefined—include warnings, suspension or revocation of business licenses, and other penalties, depending on the seriousness of the violation.

Practical Advice: Engaging with Chinese embassies, consulates and chambers of commerce

In cases where communities want to raise concerns regarding a Chinese project, the local Chinese embassy or consulate can be a first point of contact. Embassies play an important role in facilitating overseas investment. They also play a supporting role in project monitoring as well as emergency management. The Ministry of Commerce consults local embassies for project approval and Chinese companies operating abroad are required to register with local embassies or consulates.

You can raise concerns to the embassy (copying its Economic and Commercial Office, which reports to the Ministry of Commerce) in writing and request a written response and/or meeting to discuss these concerns further. You could request additional information on a project or ask the embassy to facilitate a meeting with the company. In cases where serious harms have resulted from a Chinese project, affected people could also submit a formal complaint to the embassy.

It can be challenging to engage with Chinese embassies, which often have limited experience engaging with the public and with civil society. This is beginning to change though, and there are examples of embassies responding to requests for information and meetings and in some cases even reaching out to civil society to meet and discuss concerns.