How to Research Supply Chains

What are supply chains?

Most projects produce a raw material or commodity that is sold onward for a profit. Mines produce natural resources such as coal, iron ore and gold. Large-scale plantations produce commodities such as sugar cane, palm oil and rubber. Power plants generate electricity.

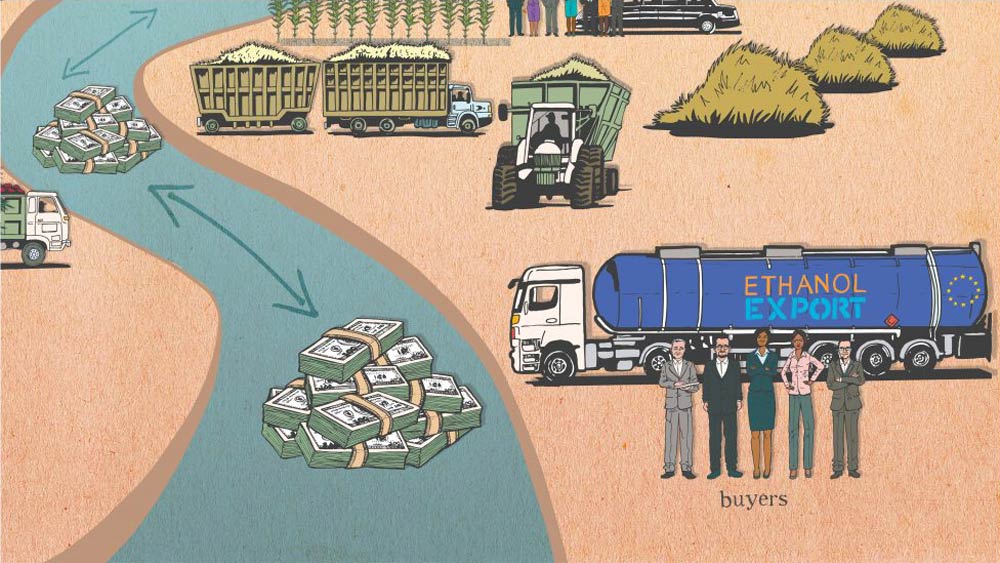

In most cases, the commodity passes through the hands of many players — traders, shippers, refiners and processors, and commodity exchanges — before it reaches end users. Taken together, these actors form a project’s supply chain. The relationships between supply chain actors are governed by legal contracts such as purchase agreements.

For instance, an oil palm plantation produces fruit that is crushed at nearby mills. From there, it is shipped to refineries, where it is processed into edible oil. Well-known consumer brands, such as Nestle and Unilever, use that oil to make products such as candy and soap. Even power plants have supply chains: Utility companies buy the electricity and distribute it to homes and businesses through transmission lines and substations.

Illustration © International Institute for Environment and Development & Inclusive Development International (2015)

Why research supply chains?

Consumer brands tend to be strong pressure points for advocacy because they have reputations they want to protect. Other supply chain actors, such as refiners that are members of sustainability initiatives, can also be strong pressure points. These pressure points can be difficult to identify because supply chains are complex and opaque, and they may be separated from the project by many layers of business relationships. By diligently following a commodity through all points of the supply chain, pressure points can be uncovered — and linked with the project causing harm — allowing you to target them in advocacy.

What makes a supply chain actor a pressure point?

If it has a reputation to protect or is a well-known brand that sells products to individual consumers.

If it is an important customer or purchases large amounts of the commodity from the company you are researching, it will have more influence over the project.

If it makes environmental and social commitments that apply to its supply chains.

If it is a member of a multi-stakeholder initiative that has environmental and social standards for supply chains, such as the Aluminum Stewardship Initiative. Some of these initiatives, such as the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, have complaint mechanisms where people can file complaints.

If it is based in a member country of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, advocates can file a complaint with a National Contact Point.

How do you research supply chains?

There are some general principles that apply to all supply chain research:

- Learn how the supply chain works: A good first step is to figure out, in general terms, how a particular commodity makes its way from a project to end users. Industry publications are good sources for this information. Are buyers, traders and other middlemen typically involved? How is the commodity usually transported? Does it get processed or refined? Once you have a general sense of how a commodity moves through a supply chain to market, you can begin filling in the details particular to your case.

- Don’t expect certainty: With a few exceptions, companies are not required to publicly disclose their supply chain relationships. In fact, these relationships are often protected by commercial secrecy rules. Given this, it is helpful to have realistic expectations about what you’ll be able to find. There are likely to be gaps — or even contradictory information — in your research. This is unavoidable. Your goal should be to gather credible evidence that can be presented to supply chain actors in a letter. In these letters, ask them to confirm or deny their relationship with the project.

- Talk to local communities: If it’s safe to do so, ask community members what they know about the supply chain. They might have heard rumors about where the commodity is being shipped. Or they might be able to see clues on the ground — like license plates, aircraft tail numbers or labels on shipping crates — that can kickstart your research.

- Open-source sleuthing: Open-source intelligence (OSINT) techniques like those used by the U.K. organization Bellingcat are helpful in supply chain research. Commodities like gold, palm oil and bauxite are physically transported to locations around the world, leaving clues that can be picked up in satellite imagery, social media accounts, and specialized airplane and ship tracking databases. For more information on these tools, see below.

The following types of sources can help with supply chain research. Note that one tool alone is unlikely to be sufficient. We recommend using a combination of these tools.

- Internet searches: Use Google or other search engines to search for references to supply chain relationships in sources such as news articles, industry analyst reports or social media sites like LinkedIn. Searching for the project or company name along with key terms such as “customer,” “buyer,” “purchase agreement” or “sales contract” can yield results. Note, though, that not all online sources are reliable. If possible, you should seek to corroborate information found online from unofficial sources with official company disclosures to stock exchanges and regulatory bodies (see next bullet point).

- Import-export data: Many countries publish data on which countries they trade with, broken down by commodity type. For instance, the European Commission maintains a database showing commodity imports that can be filtered by destination and country of origin. Governments in Africa and Asia also publish the destinations of exports, although the quality of data varies. The website Trase Supply Chains aggregates this data from around the world.

- Industry initiatives: Some industry initiatives publish information about supply chains. For instance, member countries of the Extractive Industries Transparency Index publish annual reports showing the destinations of their mining exports. Meanwhile, the London Bullion Market Association, a sustainability body for gold refineries, publishes information about source countries for gold in its Responsible Sourcing Report. For a list of these sources, see:

- Company disclosures: Public companies must regularly disclose important information about themselves to the public, sometimes including the identity of its supply chain relationships. Filings such as annual reports and offering prospectuses can shed light on a company’s customers. These documents can be found on the websites of the relevant stock exchange, the relevant financial regulatory body, or the company itself.

- Conflict mineral disclosures: The United States requires companies to file a Form SD if they use certain metals that originated in select countries in Africa. The metals are gold, columbite-tantalite (coltan), cassiterite and wolframite, including their derivatives, tantalum, tin and tungsten, originating in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Angola, Burundi, the Central African Republic, the Republic of the Congo, Rwanda, South Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia. These disclosures can be found on the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission’s website.

- Customs websites: The United States and other countries collect customs records for shipping containers that enter their borders. Several websites compile this information and make it searchable. One such website that collects U.S. customs data, ImportYeti, is free to use. Others, such as Import Genius and Panjiva, collect records from multiple countries but charge a fee.

- OSINT tools: The website of Bellingcat, which pioneered Internet-based OSINT techniques, offers guides on how to conduct investigations. Its toolkit compiles tools and sources, including social media, satellite imagery and ship and plan-tracking websites. We have collected some of the most useful OSINT tools for supply chain research in the:

For step-by-step examples of how Inclusive Development International researched the supply chains of three types of commodities, see: