What Are Investment and Supply Chains?

Behind every project — whether a mine, plantation, power plant or other infrastructure facility — is a web of actors that enable and profit from it. Taken together, these actors form the project’s investment and supply chains. Without these actors — and the money, relationships and expertise they provide — projects could not happen.

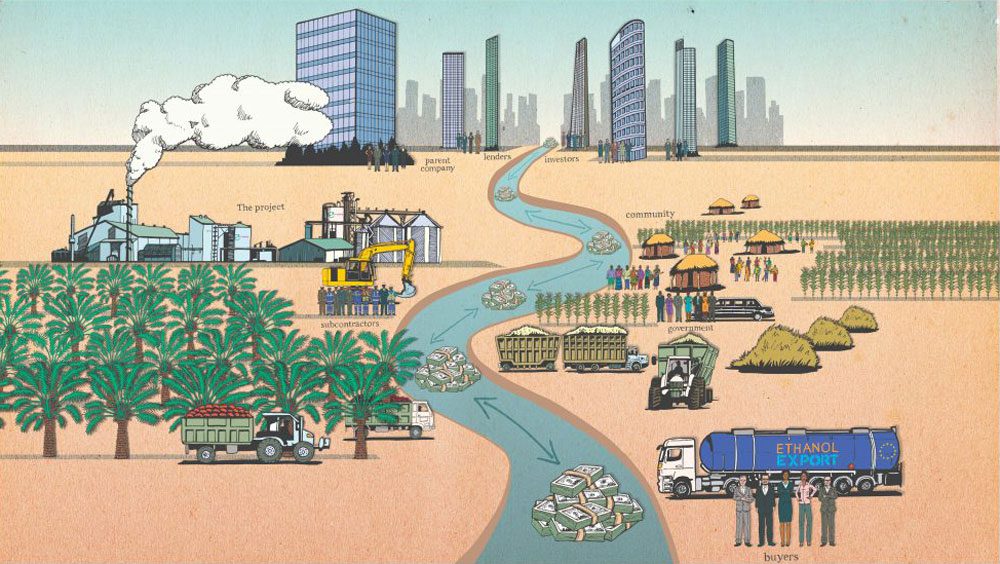

A typical project involves many types of actors, such as companies, shareholders, lenders, buyers and development banks. It can be helpful to visualize them arrayed on the banks of a river, with the project in the middle. The company developing the project sits midstream in the river, nearest to the project. Upstream is the investment chain, where financial actors like parent companies, shareholders and lenders are located. Downstream is the supply chain, where the product or raw material produced by the project flows, passing through buyers, processers and end users. Money flows in both directions, up and down the river, throughout the life of the project.

Illustration © International Institute for Environment and Development & Inclusive Development International (2015)

Why investigate investment and supply chains?

The actors, relationships and decisions that exist in investment and supply chains determine the nature of the project, including its negative and positive impacts. By investigating investment and supply chains, you can better understand who these actors are and how to influence them. You’ll also better understand what type of leverage they have over the project — and how much they can influence the situation on the ground.

For example, a substantial shareholder in a parent company can have a lot of influence over the company managing the project, both through engagement and the threat of divestment. Similarly, a major buyer can also influence the company and how it runs the project, both by raising concerns with the company and threatening to buy the product elsewhere unless these concerns are addressed.

Ultimately, investigating investment and supply chains can help you understand how to influence a company and its behaviors. This information can be used to design advocacy strategies that influence the social and environmental impacts of a project.

To learn how to analyze pressure points, see:

For advice on how to target pressure points in order to prevent harm, secure redress and influence project designs, see:

What is in the project’s midstream?

In the middle of the river — known as the midstream — is the project. The midstream is also where you’ll find the company that owns and develops the project. Normally, that company is registered in the country where the project is being developed. The company might be a subsidiary of a larger parent company. Or it might be a joint venture between two or more companies and perhaps a government.

The midstream is also where you’ll find an array of other actors that work directly on the project, including contractors, suppliers and various government entities. This part of the chain is usually at least partially visible to local communities. It is also where many decisions about land use and environmental impact are often made.

What is upstream in the investment chain?

Companies cannot develop projects without money. Much of the money to develop projects comes from actors upstream in the investment chain. These include shareholders, lenders, insurers, financial advisors and development banks.

Broadly speaking, upstream actors support a project in one of two ways. They may finance or invest in the project directly. Or they may provide general corporate financing or investment, which the company developing the project can use for any of its business activities, including funding the project itself. Understanding this distinction is important in assessing the level of influence each actor has over the project.

To learn how to uncover and analyze key actors in the investment chain, see

What is downstream in the supply chain?

Many projects produce a raw material or commodity that is sold to customers. For instance, an oil palm plantation produces an edible oil that is refined and used in consumer products like soap and candy. A hydroelectric dam, on the other hand, generates electricity that is sold to one or more buyers, often a government-run utility company.

Supply chains can be very simple — or highly complex and multilayered. Electricity supply chains tend to be straightforward, involving direct purchase agreements between power plants and utility companies. Projects that produce commodities or raw materials, on the other hand, may involve multiple layers of buyers, traders, shippers, refiners and processers, commodity exchanges, and, at the end of the chain, recognizable consumer brands.

To learn how to uncover and analyze key actors in the supply chain, see:

Relationships in investment and supply chains

Relationships between actors in investment and supply chains are important to understand. They can help you identify which actors have the greatest influence over the company managing the project. Understanding how much influence an actor has over the project is an important part of assessing its strength as a pressure point for advocacy.

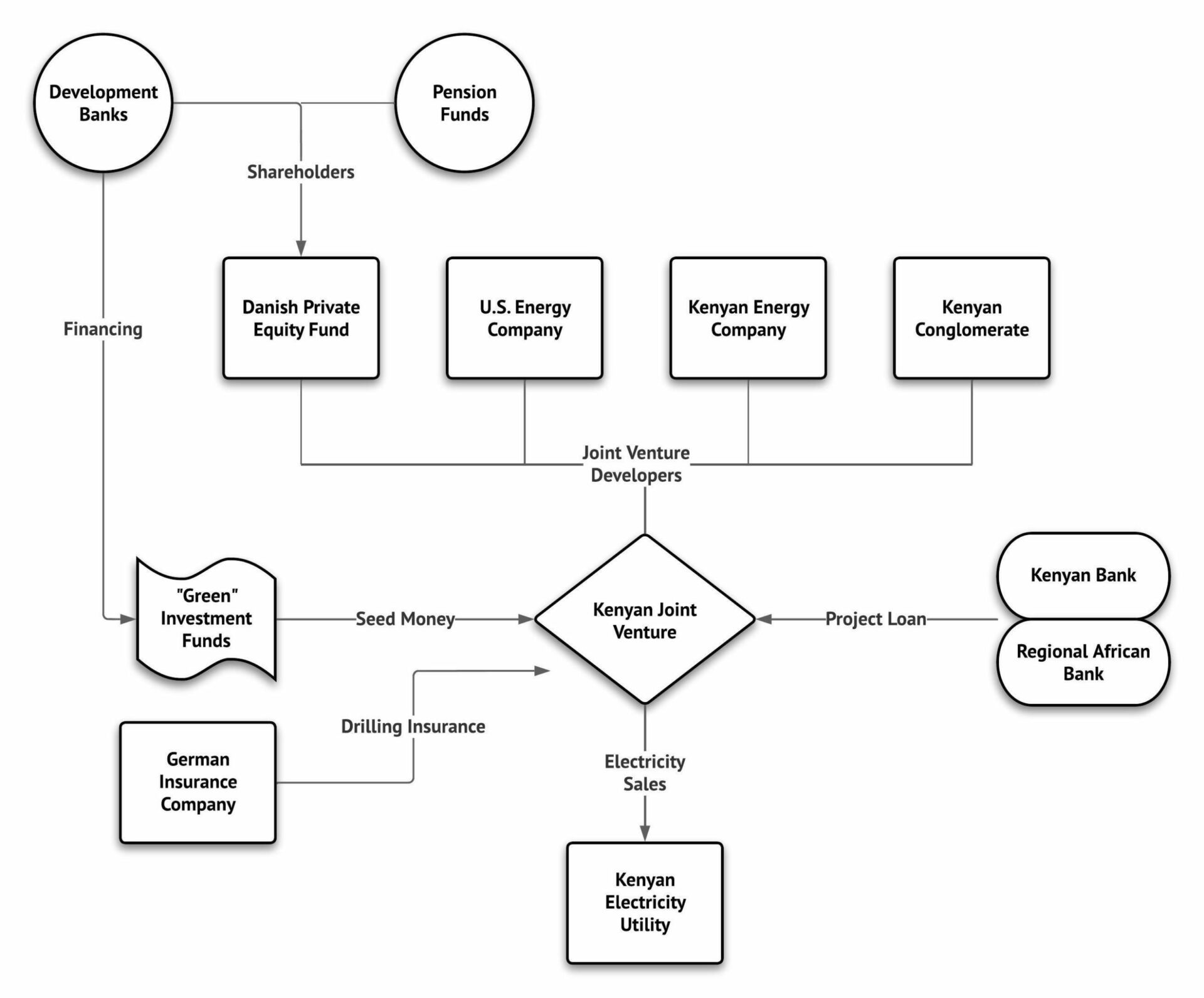

The following diagrams lay out two basic types of investment and supply chains. The first diagram, for a geothermal power plant in Kenya, shows how various actors come together to back a new infrastructure project. This includes a joint venture between three companies and a private equity fund; commercial banks that agreed to provide a project loan; an insurer that provided an exploration policy; government-backed funds that provided seed money for environmental and social impact assessments; development banks and pension funds that are shareholders in many of the entities connected to the project; and the Kenyan electricity utility, which is the plant’s only customer.

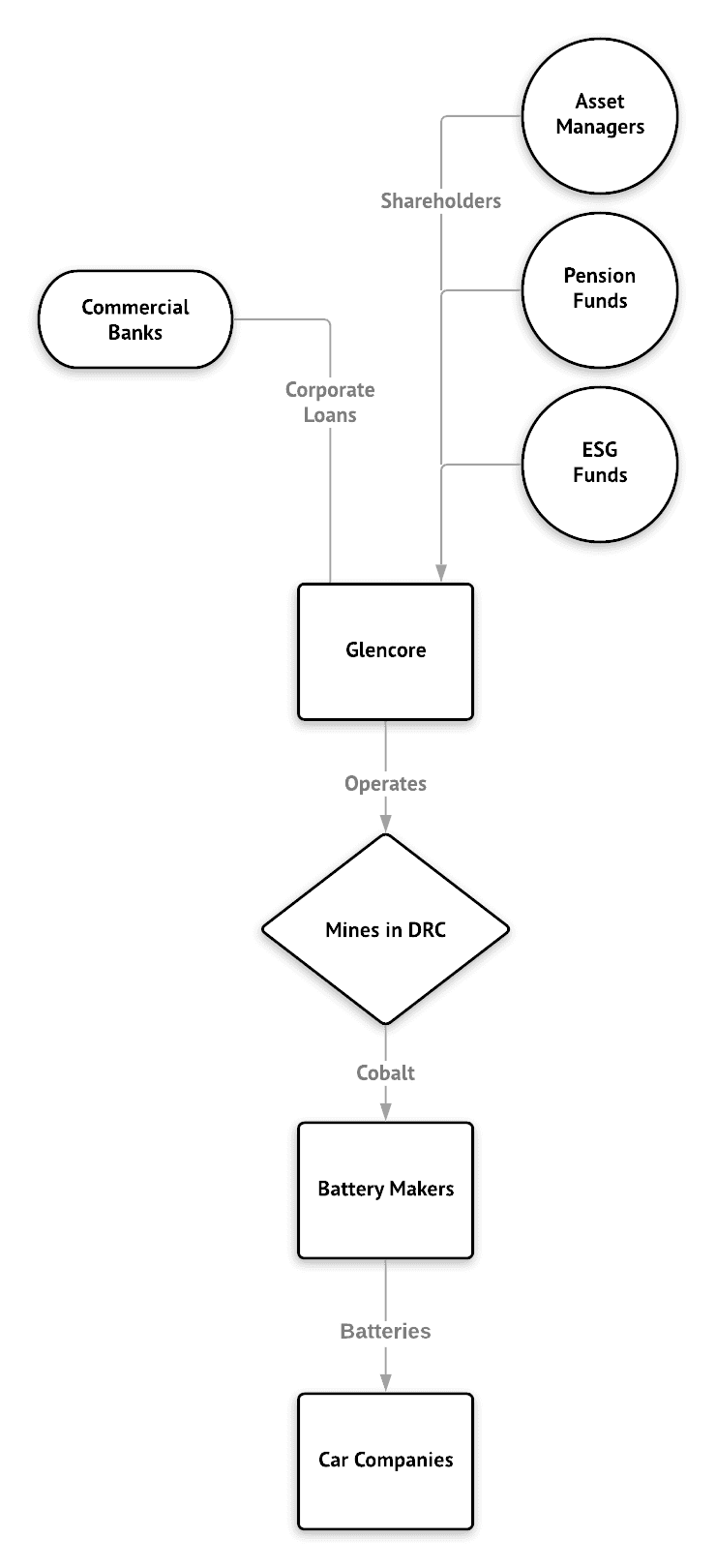

The second diagram is for a cobalt mine — a key component in electric car batteries — in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The actors in this project include a large mining company with operations around the world; shareholders in the company including asset managers, pension funds and ESG funds; commercial banks that provided the company general corporate finance; Chinese and other Asian battery makers that source cobalt from DRC; and well-known car companies that use the batteries in their electric vehicles.

At each point in these investment and supply chains, negotiations take place and decisions are made between actors.

Upstream in the investment chain, relationships between lenders and investors and parent companies are often formally agreed and set out in contracts or covenants. These agreements are usually not made publicly available, often due to client confidentiality laws that exist in most countries.

For example, when a private equity fund decided to invest in the company developing the power plant in Kenya, a negotiation took place behind closed doors, although some information was made available to the public. During this negotiation, the two actors established the terms of their relationship. The private equity fund decided how much money to invest, and whether to attach any conditions, including social and environmental requirements, to that investment.

Downstream in supply chains, relationships are also formed largely via contracts, most of which are hidden from public view. The nature of the relationships between the company and buyers varies depending on the product being sold, the size of the transaction, the size of the buyer and the company, and a number of market forces that exist both nationally and internationally. With the mine in DRC, for instance, the rapid growth of the electric vehicle market has increased demand for cobalt. This affects the relationships and agreements in the mine’s supply chain.