Uncovering a South African Mining Company’s Lenders

Inclusive Development International supported communities impacted by a gold mine in Guinea that is operated by AngloGold Ashanti, a South African multinational corporation that is listed on the Johannesburg, New York, Australian and Ghana stock exchanges.

We investigated the company in 2017. We used the following sources to uncover the company’s key lenders. By identifying these lenders, we also uncovered the involvement of a development finance institution, the International Finance Corporation, in the company’s investment chain:

Identifying the Company’s Lenders:

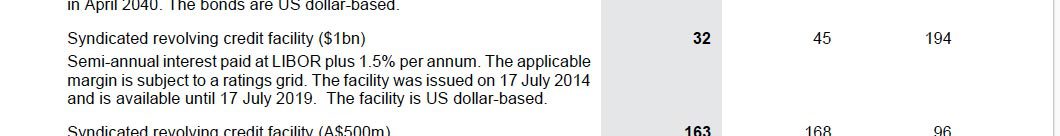

1. Company annual report: AngloGold Ashanti’s 2017 Annual Financial Statements show that the company had at least seven large loans and revolving credit facilities. The document provides some details on these transactions, including the amounts and lengths. However, the document does not identify the lenders, so we needed to do more research. We decided to focus on one transaction, because it was the largest and likely most important to the company: a $1 billion, five-year revolving credit facility issued in July 2014. Page 71 of the document contained these details:

2) Google searches: We tried a variety of Google searches to see if we could learn more. News articles in the financial press referred to several revolving credit facilities of a similar size. However, none of these deals were signed in July 2014. We learned that AngloGold Ashanti signed a facility worth $1 billion — the same amount — in July 2012. An article in the Ghanaian press reported that Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi and Barclays Bank were the lead banks on the 2012 deal:

Since companies frequently refinance such loans, we suspected that the 2014 revolving credit facility we were interested in replaced this older transaction. Some of the same banks might be involved in both deals, but we needed more information.

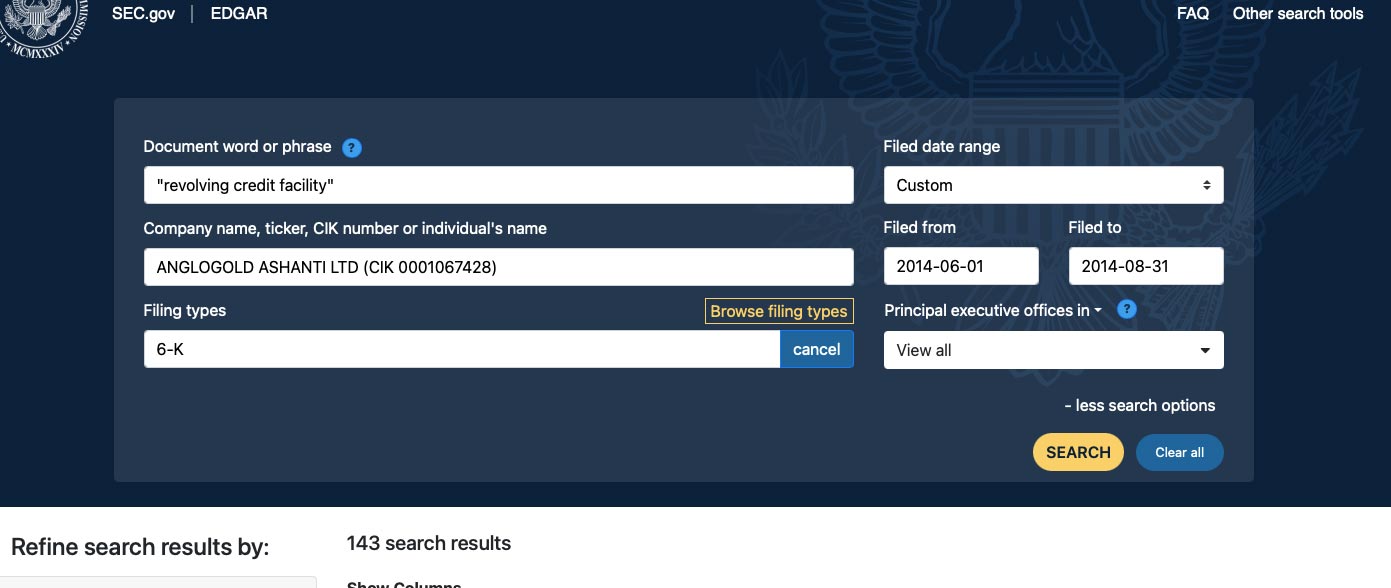

3) U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission filings: Since AngloGold Ashanti is a South African corporation that is listed on the New York Stock Exchange, it must submit any information it discloses in a foreign country to the U.S. SEC. Given the size of the 2014 revolving credit facility and its importance to AngloGold Ashanti’s operations, we suspected that the company may have disclosed details of the loan to the Johannesburg Stock Exchange, where it is also listed. If true, we knew that information would also be disclosed to the U.S SEC through a 6-K form, used by foreign companies for such information. We searched the U.S. SEC’s website for all of AngloGold Ashanti’s 6-K forms filed around July 2014, when the revolving credit facility was signed:

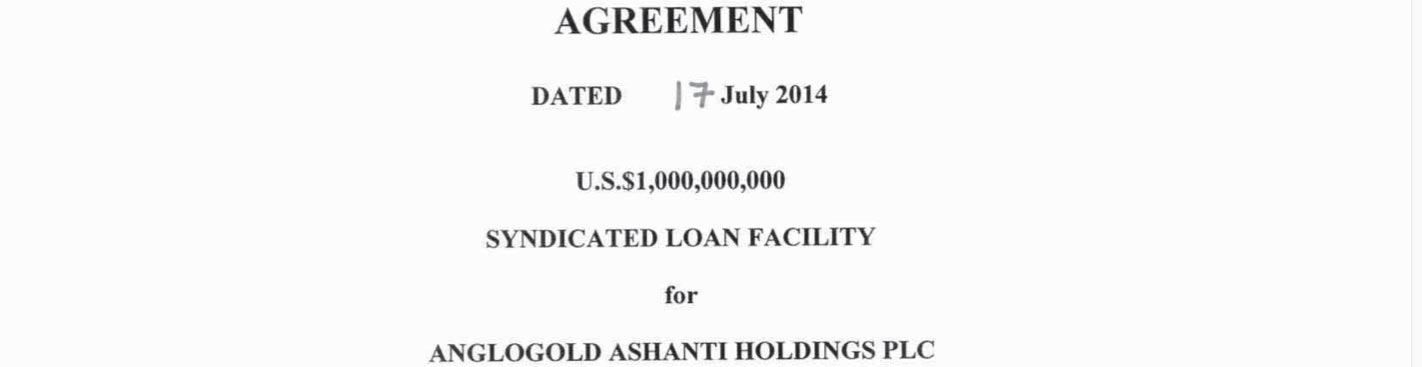

4) Review of loan agreement: The loan agreement revealed a wealth of information about the deal. Sixteen of the world’s largest banks participated in the loan. The most important of these — the lead arrangers — were Barclays and HSBC of the U.K. The agreement also revealed the purpose of the loan. AngloGold Ashanti could use the $1 billion “for general corporate purposes,” giving it full control over how to spend the money, including at the mine in Guinea. Notably, the document also contained few environmental or social provisions.

Pulling together this research, we learned the following details about the loan:

| Type of loan | Revolving credit facility |

| Amount | $1 billion |

| Tenor | July 2014 – July 2019 |

| Mandated lead arrangers | Barclays and HSBC |

| Lenders | Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi, Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, Citibank, Deutsche Bank, Goldman Sachs, J.P. Morgan, Royal Bank of Canada, Scotiabank, Standard Chartered, UBS, ANZ, Commonwealth Bank of Australia, Morgan Stanley, Bank of Nova Scotia |

Our findings were useful for several reasons. First, many of these banks were pressure points. The loan was large and important to AngloGold Ashanti, giving the lenders leverage over the company. And many of the lenders had reputations to protect and were members of voluntary environmental and social frameworks, making them susceptible to advocacy. The second reason this information was important was because it was public evidence that these banks had participated in the loan. If the banks tried to hide behind client confidentiality when we approached them — which some eventually did — we had irrefutable evidence, disclosed by their client AngloGold Ashanti, that they had an active financial relationship with the company.

We used the same techniques to uncover an agreement for another loan between AngloGold Ashanti and two South African banks. One of these banks, Nedbank, was a financial intermediary client of the International Finance Corporation, allowing affected communities to file a complaint to the Compliance Advisor Ombudsman. For details on that research, see: