A Human Rights Impact Assessment of Rubber Plantations in Ratanakiri, Cambodia

Inclusive Development International and Equitable Cambodia began working in 2013 to help more than a dozen Indigenous communities in Cambodia’s Ratanakiri province defend their collective land rights and seek redress for harms they suffered as a result of three large-scale rubber plantations that had encroached on their land and productive resources. The plantations were all owned by the Vietnamese company Hoang Anh Gia Lai (HAGL), operating through various subsidiaries.

As a starting point, we decided to conduct a human rights impact assessment to build an evidence base to support the communities’ advocacy.

So how did we do it?

Building the assessment framework

The first step was to develop a framework for the assessment by scoping out the main impacts of the project that we wanted to focus on and then determining which standards we would use to assess those impacts against. This framework was instrumental in designing our questionnaires, structuring our report and analyzing the compliance of the company against the most relevant standards.

Screening of the main issues showed that there were major problems with the development of the project, such as a lack of information and meaningful consultation of affected communities. There were significant losses of land, forest and water resources. The main impacts appeared to be on the communities’ food consumption, income and livelihoods, as well as their cultural traditions and spiritual practices. Many of the affected communities were Indigenous people, with a customary form of land tenure and food and livelihood systems that were being obstructed by the project.

The main actors responsible for the project and its impacts were the Cambodian government, the company and investors in the company. HAGL and some of its investors had committed to a set of standards that required compliance with national laws. We therefore decided to use both human rights and Cambodian law as the assessment framework.

Because many of the affected communities were Indigenous, the right of self-determination was assessed. This right is recognized in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Under these guidelines, Indigenous people have the right to give or withhold their free, prior and informed consent for any project affecting their lands, territories or resources. Information about the consultation processes and losses of lands, territories and natural resources were collected and analyzed with reference to this right, as well as Cambodian Land Law provisions that recognize and protect Indigenous land rights.

Information about impacts on food systems and consumption, and impacts on incomes and other aspects of livelihoods, were collected and analyzed with reference to the human right to an adequate standard of living, including the right to food recognized in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

Information about impacts on traditions and spiritual practices due to the loss of sacred sites was collected and analyzed with reference to the right to practice cultural and spiritual traditions recognized in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. These impacts were also assessed against Cambodia’s Land Law and Forestry Law, which provide protection for Indigenous communities’ customs and traditions.

Information about the attempts of affected communities to complain and the responses they received, including inadequate compensation as well as threats and intimidation, were collected and analyzed with reference to the right to an effective remedy recognized in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.

The particular impacts on women’s rights were assessed in relation to each of the issues and impacts above.

Designing questionnaires and conducting and recording interviews

The key informant interviews were conducted to understand the overall situation and existing issues in each village to gather data that ordinary members of the community may not be able to provide. To identify the key people in each village, villagers were asked who they thought was the most knowledgeable about important events and issues, including problems related to large-scale land concessions. The majority of key informants were village elders who were highly respected among the community, while in some cases it was the village chief or a community leader. Key informant interviews focused on community livelihoods, land tenure history, communal and household losses and impacts, compensation, consultation, perceived benefits from the company, remedies sought and future concerns about the company’s operations.

Focus group discussions were conducted with the participation of five to ten people in each village, with the facilitation of village elders, village chiefs or community leaders. These discussions focused on the impacts of HAGL’s activities, changes in each village after the operations commenced in the concession, and people’s perception about the presence of HAGL inside their village. In addition to the group discussions that included both women and men, separate women’s focus groups were held to explore specific impacts on women and children, including on their livelihoods and daily lives, food consumption, health and well-being, and safety and security.

Household interviews were conducted to collect data on household losses and impacts. In total, the team conducted 87 household interviews with affected families in 13 villages. Each interview lasted about 2 hours.

Below is a sample selection of the survey questionnaire that was used to guide and record the interviews.

Box 9: Sample sections of the recording tool used for the human rights impact assessment in Ratanakiri rubber plantation, Cambodia

DATE:

VILLAGE:

INTERVIEWER:

SURVEY NUMBER:

IS THIS AN INDIGENOUS HOUSEHOLD? Yes No

IF YES, WHICH ETHNIC GROUP?

Respondent Information

| Question | Response Category | |

| 1.1 |

Name (s)

Gender of respondent |

Male Female Both |

| 1.2 |

How old are you? |

Age in years Don’t know |

| 1.3 |

Number in household Age of children (Please give the age range of the kids) |

Men Women Children |

| 1.4 |

Primary job for household (Circle all that apply)

If other, describe |

Farming Fishing NTFP collection Timber logging Working for the concession Other |

| 1.5 | Household income | Estimated value: |

Consultation

| Question | Response Category | |

| 2.1 | Have you heard of the rubber plantation company (NAME OF COMPANY)? |

Yes No |

| 2.2 | When did you first learn about this company? |

Year Don’t know |

| 2.3 | How did you learn about this company? | Explain: |

| 2.4 | Did you have any meeting or consultation with the company about its project? |

Yes No Don’t know |

| 2.5 | If there were meetings or consultations with the community, did you attend? |

Yes No |

| 2.6 | If so, what were you told about the project and its impacts on your community? | Explain: |

| 2.7 | Did you feel you were consulted about the concession? |

Yes No Don’t know |

| 2.8 | Have you received any documents about the rubber plantation project? |

Yes No |

| 2.9 | Did you read the project documents you received? |

Yes No |

| 2.10 | Did you understand the project documents you received? |

Yes No |

Loss of land: Type of land and lost area

| Category | Lost area (ha) | When? | |

| Residential area |

Yes No |

Pre-size: Post-size: Lost area: |

|

| Rice field |

Yes No |

Pre-size: Post-size: Lost area: |

|

| Farming/orchard |

Yes No |

Pre-size: Post-size: Lost area: |

|

| Grazing land |

Yes No |

Pre-size: Post-size: Lost area: |

|

| Community forest |

Yes No |

Pre-size: Post-size: Lost area: |

|

| Spirit forest |

Yes No |

Pre-size: Post-size: Lost area: |

|

| Burial ground |

Yes No |

Pre-size: Post-size: Lost area: |

|

| Others (Explain) |

Yes No |

Pre-size: Post-size: Lost area: |

Loss of land: Type of land and lost area

| Category | Lost area (ha) | When? | |

| Residential area |

Yes No |

Pre-size: Post-size: Lost area: |

|

| Rice field |

Yes No |

Pre-size: Post-size: Lost area: |

|

| Farming/orchard |

Yes No |

Pre-size: Post-size: Lost area: |

|

| Grazing land |

Yes No |

Pre-size: Post-size: Lost area: |

|

| Community forest |

Yes No |

Pre-size: Post-size: Lost area: |

|

| Spirit forest |

Yes No |

Pre-size: Post-size: Lost area: |

|

| Burial ground |

Yes No |

Pre-size: Post-size: Lost area: |

|

| Others (Explain) |

Yes No |

Pre-size: Post-size: Lost area: |

Using participatory mapping

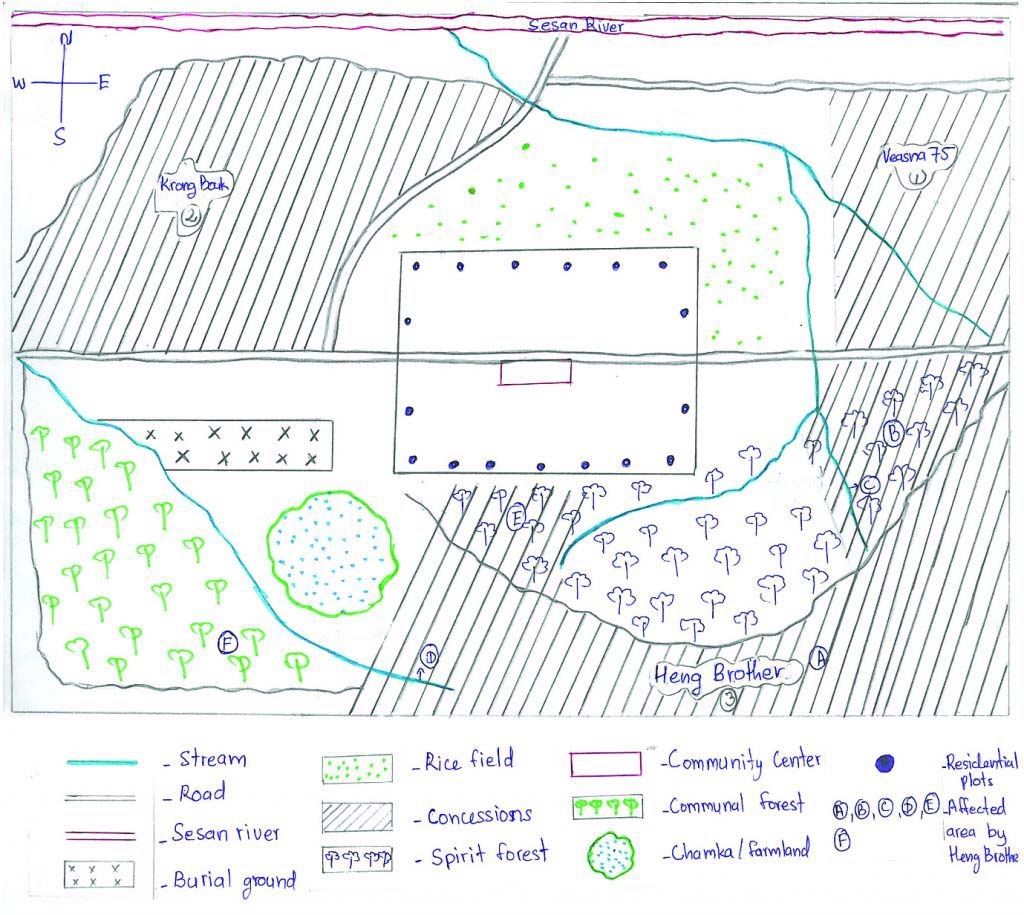

To deal with this issue, the research team facilitated participatory community mapping before using the other tools. At least five people in the village who were familiar with local geography and were most knowledgeable about the company’s activities participated in the mapping exercise. They were asked to mark on the map all types of land-use patterns (farmland, forest, streams/rivers, grazing land, burial ground, sacred sites and residential areas) and infrastructure (wells, school, roads and the community center) in the village. They were also asked to point out each company-owned plantation and their boundaries.

Structuring the report

After synthesizing and analyzing all the data that was collected during the field work and desk research, it was time to write up the findings in a report. We used the following structure:

Hoang Anh Gia Lai Economic Land Concessions: A Human Rights Impact Assessment

Chapter 1: Introduction

Describes the context and background, including general information about the affected communities and the company and its project, as well as the purpose of the impact assessment and the structure of the report.

Chapter 2: The Assessment Framework

Describes why each human right and national law was selected for the framework as well as the nature of the obligations of each responsible actor.

Chapter 3: Research Methodology

Describes the study site and villages interviewed, the data collection methods and challenges faced during the research.

Chapter 4: Impacts on the Right of Self-Determination

Describes findings on free, prior and informed consent and loss of lands and resources, and ends with an analysis of compliance with the right of self-determination and relevant Cambodian laws.

Chapter 5: Impacts on the Right to an Adequate Standard of Living

Describes findings on impacts on food and livelihoods, including jobs on the plantation, and ends with an analysis of compliance with the right to an adequate standard of living.

Chapter 6: Impacts on the Right to Health

Describes findings on physical and mental health and ends with an analysis of compliance with the right to health.

Chapter 7: Impacts on the Right to Practice Cultural and Spiritual Traditions

Describes findings about destruction of sacred sites, obstruction of traditional livelihood practices, and influence of outsiders, and ends with an analysis of compliance with the right to practice cultural and spiritual traditions.

Chapter 8: Access to Remedy

Describes problems with the court system in Cambodia and findings about attempts of communities to complain and seek remedies and the responses they received, including both compensation and threats. The chapter ends with an analysis of compliance with the right to effective remedy.

Chapter 9: Conclusion

Briefly summarizes the assessment’s overall findings and the broader lessons from these findings.

Recommendations

Contains a general recommendation to all responsible actors to use the impact assessment findings to develop a remediation plan, and then specific recommendations to each responsible actor — the Government of Cambodia, the Government of Vietnam, the company and its investors — corresponding to the nature of their obligations under the assessment framework.

Findings, recommendations and use in advocacy

The human rights impact assessment found that there were serious adverse impacts on a range of human rights. It found that the failure to seek the free, prior and informed consent of Indigenous peoples, and the confiscation of their lands and destruction of forest resources, was a violation of their right to self-determination. The report found that this also led to a violation of the right to an adequate standard of living of many affected people and a loss of sovereignty over their food and livelihood systems. The confiscation and destruction of spirit forest and burial grounds violated the right of communities to practice their cultural and spiritual traditions. The destruction of forests and pollution of streams inhibited traditional activities such as resin tapping, hunting and fishing.

The report also found that affected communities were unable to access effective remedies for these violations. Complaints to local authorities and the company were often ignored or met with threats. In some cases, the company provided compensation, but the community thought the amount was inadequate. In many cases, community members primarily wanted their land back. Many affected people did not complain due to fear of retribution and a lack of information.

After setting out these findings and conclusions, the report laid out specific recommendations to the Cambodian government, the company and its investors. The recommendations to each actor corresponded to the nature of their obligations and responsibilities under international human rights law and Cambodian law. For example, the report recommended that the Cambodian government take steps to bring the company’s land concessions and plantations into conformity with national laws, and to ensure a conducive environment for dialogue between the community and the company. The report recommended that the company immediately stop all harmful activities and engage in a good faith dialogue with affected communities in order to agree on and implement a set of remedial measures.

The human rights impact assessment and recommendations were sent to the company and several of its investors. It was used in a complaint to the International Finance Corporation’s accountability mechanism. In addition, it was used to strengthen the community’s position in a formal dispute resolution process with the company.

To read the report, see A Human Rights Impact Assessment: Hoang Anh Gia Lai’s Economic Land Concessions in Ratanakiri, Cambodia.